Rhenish lignite mining area - Landscape change

Energy

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 74 | Ill. 2

Overview

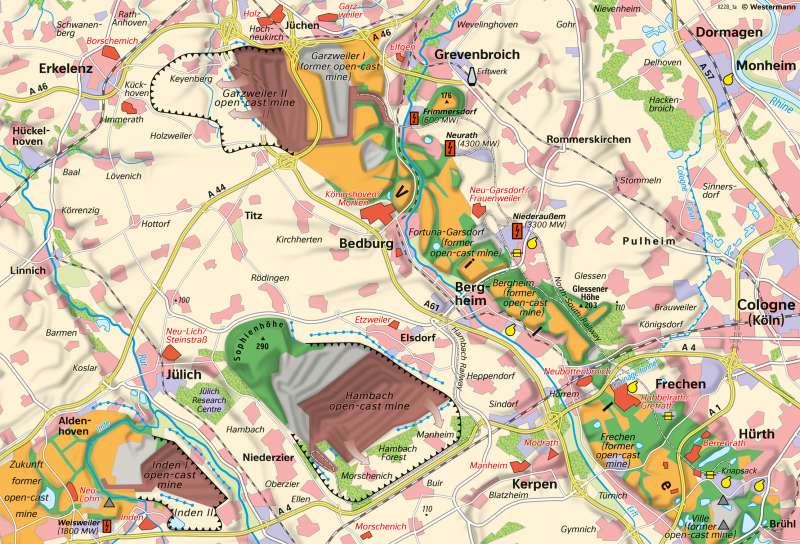

The impact of expanded lignite mining operations in the Lower Rhine Basin exhibits a regionally differentiated structure. Three factors have contributed to these changes: preparations for mining, actual mining operations and recultivation measures.

Start of large-scale mining

The first preparatory step for large-scale lignite mining in the Lower Rhine Bight was defining the future mining area with the lignite plan, which was drawn up and approved by the lignite committee in 1979. For mining, a complete drainage of the hanging strata and of the coal seam itself as well as an easing of the pressure water in the overburden were necessary.

Due to the large-scale mining, numerous villages and individual farms had to be resettled. With a few exceptions, such as Habbelrath, Grefrath and Berrenrath, the affected settlements joined central towns at the request of the inhabitants and in accordance with the state planning. This way, Garzweiler, for example, became a district of Jüchen. In addition, the relocation of traffic routes was necessary. Among others, this affected several roads east of the Erft and the motorway section between Cologne and Düren.

Land utilisation conflicts

Land utilisation conflicts often emerge within the context of lignite mining operations, as was the case in the Rhenish mining region. Whereas brown-coal mining once competed primarily with forestry, its most important competitor today is agriculture. One argument in favour of lignite production is the fact that coal accounts for 30 percent of the German electrical power mix (2019). Therefore, it is also still more important than wind farms and solar parks (see chart below). Justified claims are expressed on the other hand by farmers, who run market-oriented, capital-intensive agricultural operations on an above-average scale on largely nutrient-rich loess plates measuring up to seven metres in thickness on lands around the Jülich Boerde, including the northern section of the Villehorst. Producers of food and semi-luxury food products, such as sugar and canned goods, have also formed alliances with these farmers.

The present land utilisation conflict is exacerbated by a number of circumstances, including the discrepancy between the demand for arable land and the availability of recultivated land and the exploitation of ecologically valuable areas such as the Hambach Forest for mining purposes. Conflicts between the brown-coal industry and other potential users are also fuelled by the fact that, as part of the fringe zone of the urban agglomeration known as the "Southern Rhine Track" is covered by a dense web of roads and highways and also has an above-average population density. For these reasons, it is subject to increasing pressure to promote the development of new housing, industrial and commercial areas (suburbanisation).

In addition to the negative impact of opencast mining on groundwater levels, emissions from fossil-fuel power plants and the local basic materials industry also contribute to environmental pollution.

The example of the Hambach opencast mine

The Hambach opencast mine is located between Jülich and Bergheim in the centre of the Rhenish lignite mining area. Mining began in 1978, and today the mining field is around 370 metres deep; another 1,25 billion tonnes of lignite are still stored underneath. At the end of 2017, the Hambach opencast mine had an operating area of around 4500 hectares; almost 1500 hectares had already been recultivated (1442 hectares for forestry, 14 hectares for agriculture).

Around 40 million tonnes of lignite are extracted from the Hambach opencast mine each year. It is transported to the power plants in Niederaussem, Frimmersdorf, and Neurath by the Hambach railway; due to the expansion of the mining area, the railway line had to be relocated to the south in 2012.

Landscape recultivation

Outstanding examples of the recultivation measures that have given a new face to a landscape that had been ravaged by opencast mining are those undertaken in the southern district, where mining operations were discontinued following the depletion of coal deposits at the Ville mine south of Goldenberg in May 1988. All of the standard approaches to recultivation are found here in close proximity to one another. The basis for forest recultivation efforts since 1960 is forest gravel, a mixture of Pleistocene sand, gravel, and loess, which forms a layer measuring four metres in thickness. Valuable native trees such as beech, oak and evergreens as well as smaller stands of deep-rooted black locust, alder and poplar were planted on this foundation. Most of the remaining pits were filled to form lakes. Sixteen of these lakes are located in the area south of the motorway between Cologne and Düren alone. These forested areas and lakes are now part of the Rhineland Nature Park, a local recreation area serving the greater Cologne-Bonn metropolitan area. Other pits were converted to dumping grounds and landfills for household waste, power plant ash and hazardous waste (e.g. Ville).

The first step in landscape recultivation was to spread a two-metre-thick layer of loess using a dry application process. The fields were then cultivated during a seven-year preparation phase for the purpose of activating biological processes in the soil before being turned over to local farmers. Soil quality is warranted for a period of 25 years. In some places, such as the Berrenrath Hamlet, fields are farmed from new settlements consisting of between six and ten farms, as this form of settlement is more advantageous than single-farm operations in the midst of the cultivated areas.

Power generation

The five power plants located in the region are counted among the industries based on lignite extraction. In 2012, more than 90 per cent of the German lignite mined was used to generate electricity and district heating, while a smaller proportion is used in refining plants where it is processed into lignite dust for large combustion plants (corresponding factories in Frechen, Fortuna, Berrenrath), briquettes and much more. Furthermore, energy-intensive industries such as aluminium and chrome smelting and the chemical industry have settled at locations in the lignite mining district or in the surrounding area.