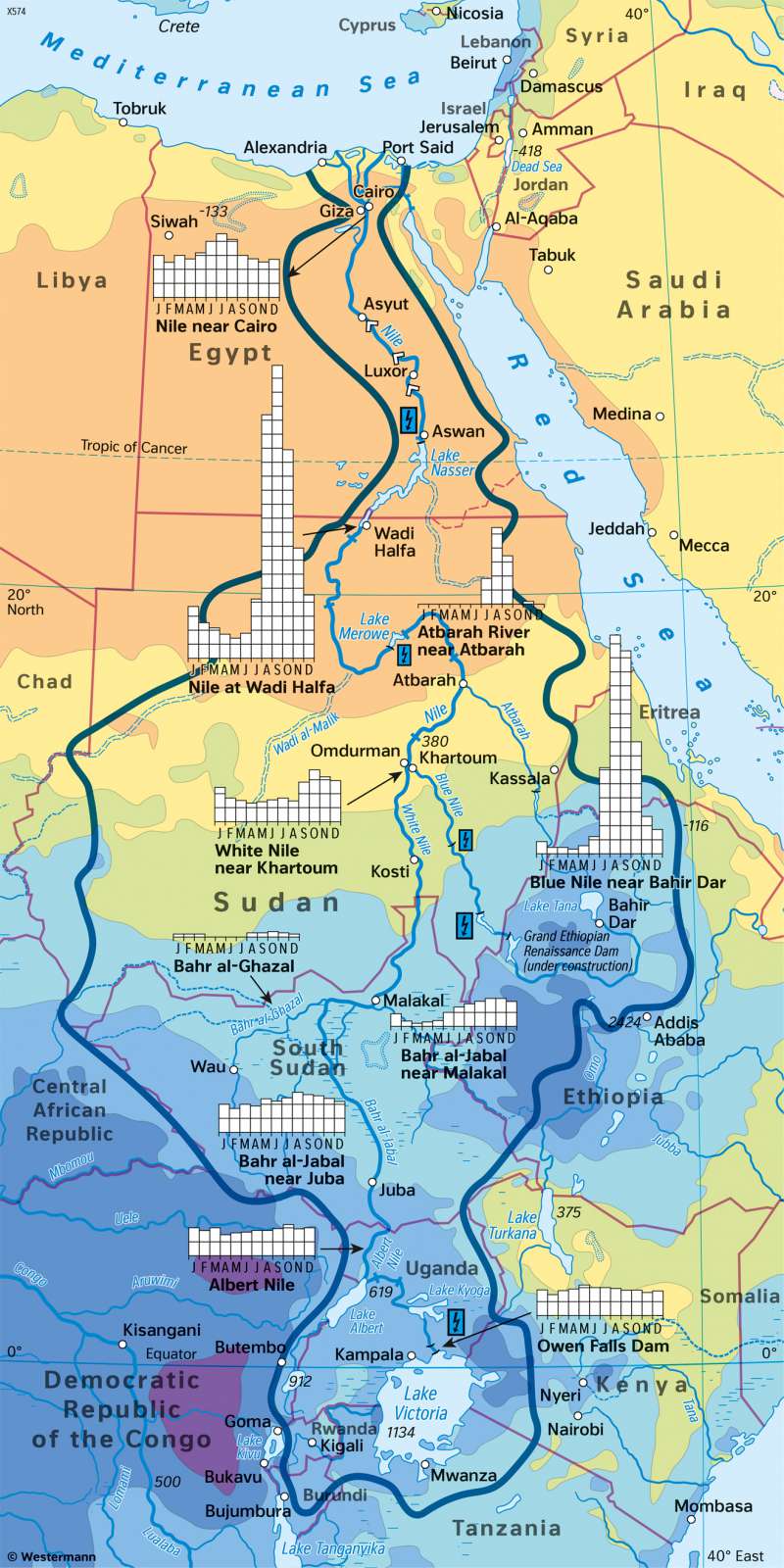

The Nile - River basin and runoff

Climate and Nile catchment

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 147 | Ill. 7

Overview

The flow of the Nile can be explained on the basis of natural (climate, relief, natural lakes) and anthropogenic factors (abstraction of water for irrigation purposes, construction of dams and locks).

The Nile River basin can be divided into four typical climatic zones from south to north. The headwaters of the White Nile are located in the tropics with year-round rainfall. The Kampala station and Owen Falls Dam are an example of this. To the north, this is followed by the zone of the seasonally humid tropics (see Bahir Dar station). There, precipitation is also still very high. However, there is a typical division into rainy and dry seasons. The further north you go, the lower the rainfall (see Khartoum station). In the desert areas, there may even be no rain at all (see Aswan station). Finally, the coastal area along the Mediterranean Sea forms a transition zone in which precipitation is already higher than in the zone of deserts and semi-deserts (see Cairo station). However, they are still very low and do not reach the values that are typical in the rest of the Mediterranean region or in the zone of the savannas of northern Africa.

Hydology of the Nile

Parts of the Central African Threshold, the northern East African Highlands and the Ethiopian Highlands stand out as having particularly high precipitation. Here, altitude and exposure are noticeable. As a result, instead of a strict climate zones and thus areas of equal precipitation, a more mosaic-like, relief-oriented spatial arrangement can be observed.

As a result of these factors, the drainage of the Nile above Aswan is essentially a reflection of the precipitation and its annual course in the catchment basin of the White Nile, the Blue Nile and their tributaries. In the upper course of the White Nile between its headwaters and the mouth of the tributary Bahr al-Arab near the city of Malakal, there are no significant fluctuations in discharge during the course of the year. A balancing effect results from the East African lakes (above all Lake Albert, Lake Kyoga and Lake Victoria, from which the White Nile is fed).

The tributary of the White Nile flowing from the east near Malakal, but above all the Blue Nile, can easily be linked to the maxima and minima of precipitation in the region. The highest amount of drainage of the Blue Nile are reached in August and September, somewhat offset in time from the months with the highest precipitation, July and August. The lowest values can be observed between January and June and are a consequence of the dry season in the region. This is comparable to the Atbara River further north, which, as a seasonal water-bearing river, only contributes significant amounts to the Nile's discharge in the months of July to September.

The drainage diagram of the Nile above Aswan results from the sum of the drainages of the White Nile and the Blue Nile, which flow into each other near Khartoum. This shows a maximum in the months of August to October - offset in time compared to the Blue Nile. The minimum in the months of February to June is not as pronounced as it is in the Blue Nile. Here, the year-round water flow of the White Nile has a balancing effect.

Below the Aswan Dam, the Nile shows a very balanced drainage. The dam impounds a huge water reservoir up to 70 metres deep. At more than 550 kilometres long (almost the distance between Luxembourg and Prague, as the crow flies) and up to 10 kilometres wide, Lake Nasser covers an area about twice the size of the Saarland. Lake Constance, Germany's largest lake, is only about a tenth as large at 536 square kilometres.

Lake Nasser was created between 1958 and 1970:

- to enable permanent irrigation in the Nile oasis between Aswan and the delta, to extend the cultivation period to the whole year (several harvests) and to be able to expand the irrigated land as a whole,

- to generate electricity all year round,

- improve navigation on the Nile,

- to build up water reserves to reconcile dry years, which occur regularly,

- to improve flood protection for the settlements downstream.

To achieve these goals, not only high investments were made, but also risks and disadvantages were accepted. These include, for example, the fact that since the beginning of the 1970s, farmers downstream of the dam no longer have access to fertile Nile mud, which until then had naturally fertilised their land in the course of the annual floods. They were therefore forced to use artificial fertilisers instead.