Maloelap (Marshall Islands) - Vulnerability of an atoll

Atmosphere and climate change

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 21 | Ill. 6

Overview

The Maloelap Atoll lies north of the equator in the Tropical Zone. The prevailing wind direction is northeast due to the trade wind circulation.

Atolls are ring-shaped or oval coral reefs with islands rising above sea level and a lagoon in the middle. Stony corals and calcareous algae form the reef community. Certain ecological conditions are necessary for coral reefs to thrive: the seawater must have a minimum temperature of 20°C and a salinity of around 3.5 per cent, and it should also be oxygen-rich, strongly agitated and sufficiently exposed to light. Corals can be found up to a water depth of 25 metres.

Theory of atoll formation

The formation of atolls is explained by a theory of Charles Darwin. During the slow sinking of a volcanic island, first a fringing reef, then a barrier reef forms. The reefs consist of the skeletons of dead corals. Reef growth of 1 to 25 millimetres per year keeps pace with the subsidence so that the reef surface always remains close to the sea surface. When the volcanic island finally submerges completely, a lagoon takes its place. It has several passages to the open sea on the lee side, through which water that has entered the lagoon can drain away again. They serve as an entrance for ships into the protective lagoon.

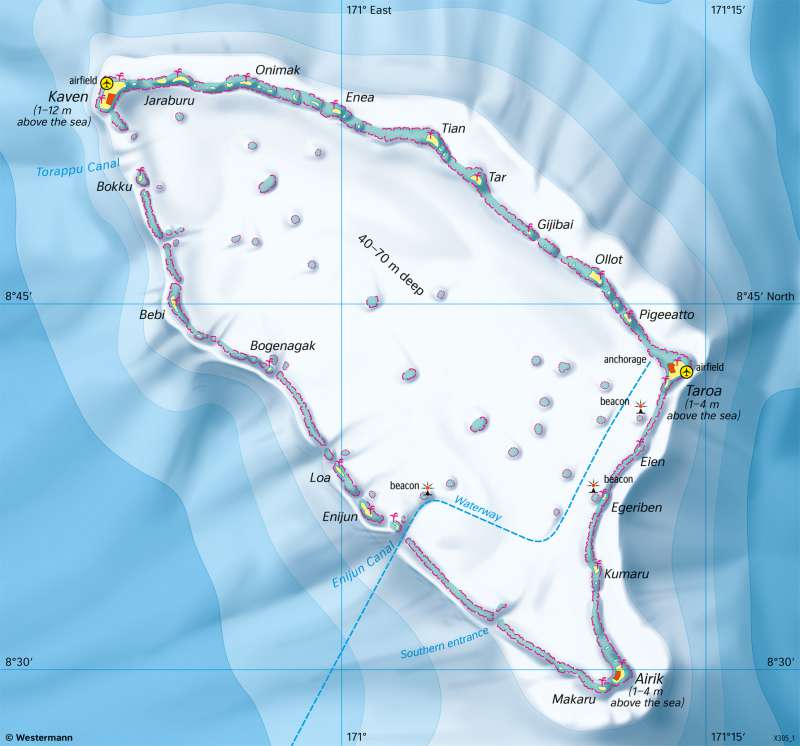

Maloelap Atoll

The atoll's land surface is formed by narrow, elongated islands. It is very small: with a lagoon area of 973 square kilometres (slightly larger than Berlin), Maloelap Atoll has only about 10 square kilometres of land area (1400 football fields). Due to the meagre living conditions, remote atolls are only sparsely populated. Around 800 people live on Maloelap. The economic basis is the cultivation of coconut palms and taro as well as collecting marine animals.

The ring of reefs surrounding the lagoon acts like a breakwater. Individual islands stick out one to four metres above the high tide line. The low elevation above sea level explains the vulnerability of the atoll and its inhabitants to sea-level rise. There is a danger that the growth of the reef will not be able to keep up with the sea level rise. Then the reefs can no longer perform their function as breakwaters, increasing the risk of flooding during storms. Areas that are now up to 70 centimetres above sea level could even be permanently flooded by the end of the century.