Amazonia - Tropical rainforest in retreat

Economic development and nature conservation

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 197 | Ill. 3

Overview

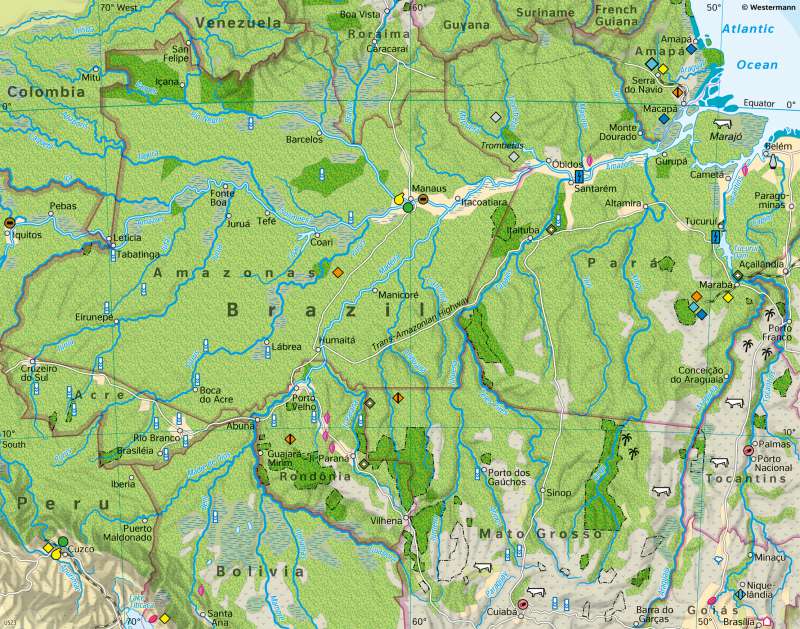

The area shown in the maps is divided into three parts: In the centre, there is the Amazon basin, naturally covered by tropical rainforests. This is still predominantly recognisable in 1980. In the south of the map section, the zone of tropical rainforests merges into the zone of wet savanna. Due to their natural and climatic conditions, the wet savanna and the transition zone to the rainforest are excellently suited for agricultural use and have therefore already been very strongly modified and reshaped by anthropogenic use. In the southwest, the high mountain range of the Andes encloses Amazonia from the Pacific.

Beginnings of exploitation

The economic exploitation of Amazonia began in the second half of the 19th century with the extraction of rubber. However, its destructive dynamics did not unfold until around 1970, when the construction of a long-distance road through the southern Amazon, the Trans-Amazonian Highway (Transamazônica), began, which was later supplemented by other long-distance roads. Although initial development attempts largely failed, they marked the beginning of decades of large-scale encroachment on the tropical rainforest. A major economic motive for development was and still is timber, for example mahogany. This hardwood, of great durability, was widely used in the industrialised countries, for example in window and furniture construction. In the course of time, far more than 2000 timber companies, mostly of foreign origin, participated in the exploitation of the tropical forest. Even though the trade in mahogany is now restricted by international agreements (importation is subject to authorisation in Germany), logging continues on a large scale, often illegally. From about 1975 onwards, with the support of the government, there was large-scale forest clearance in the southern fringes of Amazonia and along newly constructed roads. Much of this clearing was carried out by immigrant agrarian colonists who wanted to gain land for agricultural cultivation or cattle ranching. Agrarian colonisation advanced from the south along the transport axes into the states of Rondônia, Mato Grosso and Pará. In parallel, the population increased rapidly. A third cause for the destruction of the tropical forests proved to be the exploitation of mineral resources. The discovery and mining of huge iron ore deposits and important deposits of gold, tin, asbestos, bauxite and oil, for example, led to ever greater encroachment on the rainforest (e.g. in the region around Carajas). All three processes, logging, agrarian colonisation, and resource extraction were and are closely linked. For example, illegal land grabbing often follows the routes that were created for logging or ore transport.

The price of overexploitation

As long as the tribal territories of the still about 100,000 indigenous people of Amazonia were located in areas that could be exploited economically in any way, they were ruthlessly displaced. Some tribes now live in protected areas, but they are often threatened with loss of cultural identity or disappearance. Another consequence is the reduction of evaporation and the resulting decrease in precipitation, which could lead, for example, to changes in the annual cycle of precipitation with atypical dry phases. Furthermore, a dramatic increase in soil erosion can be observed in the clearing areas. The washouts not only lead to a considerable loss of nutrients, but also to many rivers in the Amazon region being discoloured brown by masses of mud. No less dangerous, especially for the rivers and their inhabitants, are contaminations by petroleum and by highly toxic chemicals and metals, such as mercury, which are used in the mining of bauxite, gold and other raw materials and enter the rivers in large quantities. Incalculable are the consequences for the world's climate, which are to be expected from the destruction of the Earth's "green lungs" and the resulting increase in the CO2 content of the Earth's atmosphere

Current developments

In recent decades, several developments in the field of agriculture have intensified and now play a major role in the deforestation of Amazonia, especially in the south:

- cattle farming on large farms

- the expansion of cultivation areas for soya, which is used as concentrated feed in cattle and pig fattening

- the boom in biofuels, here especially the cultivation of the raw material sugar cane.

The Brazilian government is also pushing the economic development of Amazonia in the areas of industry and services. Proof of this are the free trade zones along the Amazon. Manaus in particular now has a comparatively broad industrial base. The city also benefits from its direct accessibility by ocean-going vessels across the Amazon and the oil and gas deposits in western Amazonia. The deforestation of Amazonia has progressed rapidly since the beginning of the development. In the state of Mato Grosso, about one percent of the land area was affected by deforestation in 1975, in 1980 it was already more than six percent, and today more than three quarters of the original rainforest areas have given way to pasture and arable land. The situation is similar in the states of Pará, Rondônia and Maranhão. In the states of Amazonia and Amapá, on the other hand, the proportion of forest is still relatively large. According to official figures, between 4,500 and 6,000 square kilometres of forest are currently destroyed each year in Amazonia, which corresponds to 2 to 2.5 times the area of Saarland. Since about 2005, the annual deforestation rates have been decreasing significantly. Environmentalists assume that there is a considerable number of unreported cases of cleared areas that are not officially recorded. The map shows a relatively large proportion of protected areas for indigenous people. They are - often in contrast to their surroundings - almost completely forested. However, the large number of illegal encroachments and forcible displacements suggests that forest loss is also occurring here. Outside the protected areas, there are significant closed rainforest areas without special protected area status in the states of Amazonas and Acre. It is to be feared that logging, agricultural colonisation and raw material extraction will penetrate these areas in the coming decades (from the south, along the roads or the Amazon).

The price of overexploitation

As long as the tribal territories of the still about 100,000 indigenous people of Amazonia were located in areas that could be exploited economically in any way, they were ruthlessly displaced. Some tribes now live in protected areas, but they are often threatened with loss of cultural identity or disappearance. Another consequence is the reduction of evaporation and the resulting decrease in precipitation, which could lead, for example, to changes in the annual cycle of precipitation with atypical dry phases. Furthermore, a dramatic increase in soil erosion can be observed in the clearing areas. The washouts not only lead to a considerable loss of nutrients, but also to many rivers in the Amazon region being discoloured brown by masses of mud. No less dangerous, especially for the rivers and their inhabitants, are contaminations by petroleum and by highly toxic chemicals and metals, such as mercury, which are used in the mining of bauxite, gold and other raw materials and enter the rivers in large quantities. Incalculable are the consequences for the world's climate, which are to be expected from the destruction of the Earth's "green lungs" and the resulting increase in the CO2 content of the Earth's atmosphere