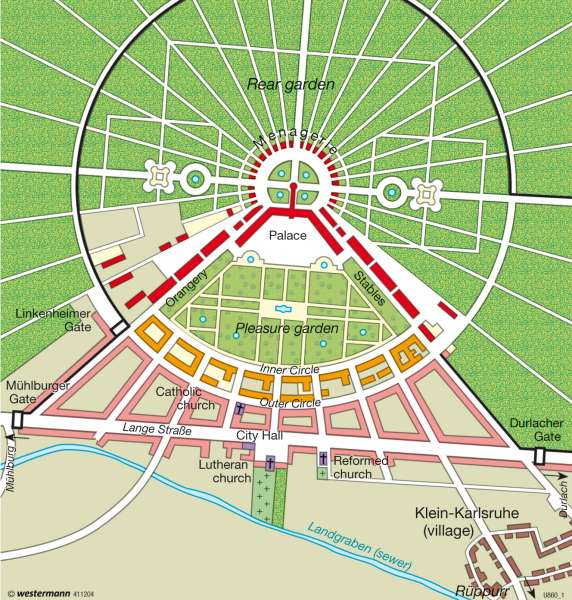

Karlsruhe circa 1740

Europe - The modern age

978-3-14-100790-9 | Page 33 | Ill. 5

Information

The majority of cities in Europe north of the Alps came into being during the Middle Ages. The ruling seat of a sovereign — for example a castle — often formed the nucleus around which craftsmen, merchants and peasants settled. The principle of founding a city around a ruling seat repeated itself in the age of Absolutism.But the cities that came into existence in the Baroque era of the 17th and 18th centuries have a different character. They are planned cities designed on a drawing board; their structure is often oriented on the ruler's residence and is thus designed to underline his claim of absolute power. Well-known examples of planned Baroque cities in Germany are to be found especially in Baden-Württemberg: Freudenstadt (from 1599), Ludwigsburg north of Stuttgart (from 1704) and Mannheim (from 1720). Erlangen in Bavaria (from 1686) and Bad Karlshafen in Hesse (from 1699) are further well-known examples of planned cities. But the classic example is Karlsruhe, also in Baden-Württemberg, with its spoke-shaped structure (from 1715).

City Foundation

The city of Karlsruhe stems from an idea by the Margrave Karl III Wilhelm of Baden-Durlach. The original residence of the margraves in Durlach was destroyed in 1689. Instead of having the castle rebuilt against the wishes of the populace, Karl III Wilhelm decided in favour of a generous new construction a few kilometres to the west. As his model the margrave took Versailles, which had been built just a few years previously under the French King Louis XIV. In 1715 the foundation stone was finally laid for the Karlsruhe Palace, around which the remaining elements of the planned city were oriented. By 1717 the palace was sufficiently complete for the margrave to hold audiences there. This signalled the end of Durlach as a residence city.

City Structure and Development

Karlsruhe is laid out in a radial pattern. The palace forms the centre, from which 32 streets lead away. To the south the layout opens out in a fan shape. The pleasure garden is enclosed by the buildings of the Orangerie and the royal stables; houses for the royal household and members of the aristocracy, arranged in a crescent, serve as demarcation. Adjoining this complex are town houses aligned along nine streets. Lange Straße, the street running from west to east, marks the clear boundary to the areas used for agriculture and the districts occupied by craftsmen and day labourers. Both of its ends are guarded by gates.

The area lying to the north of the palace is devoted to nature. The Hardtwald forest, a game reserve as well as a Fasanerie (pheasant house) and a menagerie served the margrave as recreational areas for hunting or other pursuits.

Residents who moved to Karlsruhe were accorded special privileges. The practice of all Christian religions was permitted — a Catholic, a Lutheran and a reformed church can be seen on the map. Supra-regional recruitment also attracted people from far away; some even came from France and Italy. In 1719 Karlsruhe already had 2,000 inhabitants. But further growth was slow — by 1750 only another 500 new citizens had been added.

D. Falk; Ü: J. Attfield