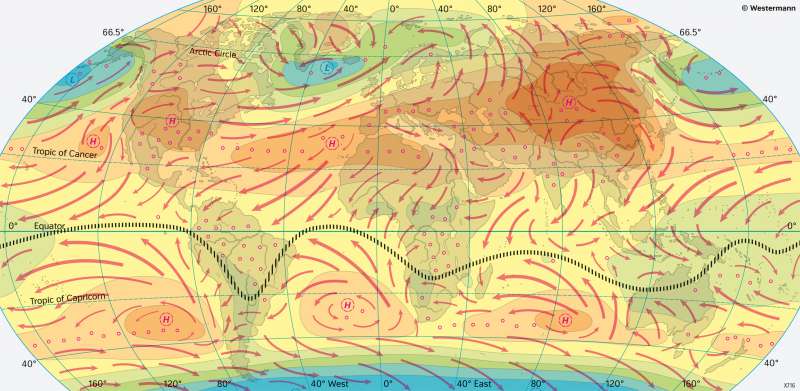

The World - Air pressure and winds in January

Climate elements

978-3-14-100890-6 | Page 18 | Ill. 5

Overview

The maps give an overview of the mean near-ground air pressure conditions and the resulting wind conditions in January and July worldwide. The different air pressure fields are limited by isobars (lines of equal air pressure). The red arrows indicate the prevailing wind directions.

Air pressure and wind fields

The atmospheric circulation strongly depends on the position of the various pressure formations. Due to the deflecting force of the Earth's rotation, the Coriolis force or Coriolis deflection, the air does not flow directly from the high to the low-pressure area. It rather circulates around the pressure formations depending on the differences in air pressure and the ground friction. In the Northern Hemisphere all air movements are deflected to the right, in the Southern Hemisphere to the left. Therefore, in the Northern Hemisphere, winds move counterclockwise around low-pressure areas and clockwise around high-pressure areas. In the Southern Hemisphere, the situation is exactly opposite. If an air mass crosses the equator, its direction of movement changes accordingly. In this way, the southeasterly trade wind over the Indian Ocean is diverted to a south-west monsoon in the area of the Arabian Sea.

The comparison of the air pressure and winds in January and July clearly shows the seasonal shift of the system, which follows the zenith position of the Sun with a certain delay. The pressure formations ultimately result from the difference in energies at the equator and the pole. The associated balancing currents lead to the formation of the subpolar low-pressure trough and high subtropical high-pressure cells. For this reason, the individual links of the atmospheric circulation shift northwards with the solar noon in the northern summer and southwards in the southern summer - thus following the area of strongest energy supply.

Seasonal contrasts

In January, the dark blue areas of low air pressure stand out clearly above the North Atlantic, the North Pacific, and the Antarctic low-pressure trough. Westerly winds prevail between these subpolar low-pressure areas (for example, the Icelandic or Aleutian low) and the subtropical high-pressure areas (for example, the Azores and St Helena Highs). These are particularly strong in the winter of the respective hemisphere, as the energy contrast equator/pole is greatest then. In the interior regions of Asia, the prevailing westerly winds are blocked by a strong cold high near the ground. Above North America, such a continental high is only relatively weakly formed.

From the subtropical high-pressure areas, the winds deflected to northeast or southeast trade winds flow into the equatorial low-pressure trough. This makes up the confluence area (confluence) of the trade winds, which, as the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), marks the area of the strongest tropical precipitation. Above the continents, the equatorial low-pressure trough is more prominent and shifts seasonally more to the north or south compared to areas above the oceans. Above land areas, the trade winds resulting from descending air movements of subtropical high-pressure areas are very dry, such as in North Africa or above India in the winter ("northeast monsoon"). If, on the other hand, they first sweep over larger areas of sea, the moisture absorbed in the process can lead to high precipitation when it passes over land, as can be observed on the east coasts of Brazil, South Africa, Madagascar, and Australia.

The persistent subtropical high-pressure belts, which are predominantly anchored over the oceans, also significantly control the ocean currents. Cold water masses are transported towards the equator on their eastern side and warm water masses towards the poles on their western side.

In September and March, the subtropical highs shift quite abruptly from their summer to their winter position and vice versa. In July they have reached their northernmost position. In the process, they strengthen in the respective winter hemisphere. However, the seasonal change mainly affects the pressure conditions above the continents. Thus, the Asian cold high in the winter is by a pronounced thermal low above the highlands of Tibet replaced in summer. It directs the southwest monsoon far inland. Hardly any thermal high- and low-pressure areas form above the continents of the Southern Hemisphere - their area is too small compared to that of the surrounding seas.