Upper Engadin (Switzerland) — Alpine tourism in a changing environment

Southern Europe - Tourist destinations

978-3-14-100790-9 | Page 79 | Ill. 3

Information

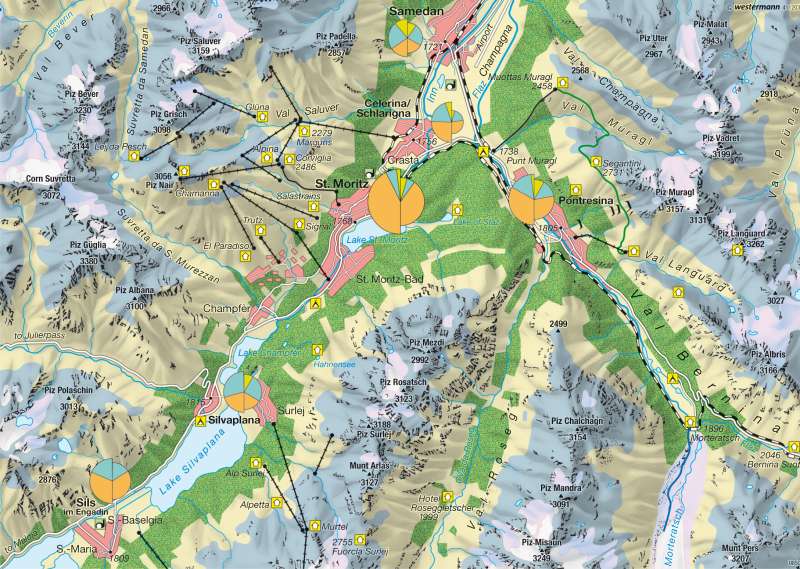

The Upper Engadin Valley is one of the most heavily populated valleys in Europe. The cool but sunny climate, natural surroundings and excellent tourism infrastructure make this valley into one of the most popular tourist destinations. The number of overnights shows that more tourists visit the Upper Engadin in the winter season than in the summer. Winter tourism is traditional in this region. St. Moritz regards itself as the "birthplace" of winter tourism. While most overnights in St. Moritz, Pontresina and Sils im Engadin are registered in hotels, in other localities a high proportion of tourists find accommodation in holiday homes or apartments, on camping sites or in youth hostels. The huge demand for second homes, for example, causes problems due the pressure it puts on the local housing market.In recent years, investments have not only been made in infrastructure, but a lot of money has also been spent on defence measures. Two avalanche barriers have been built in Pontresina to protect the population from rock slides and avalanches. In Samedan the river Flaz is being diverted and at the same time also largely returned to nature. The aim is to give the community better protection from flooding in future.

The population of the Upper Engadin lives under permanent threat from the forces of nature. Global warming may intensify this threat. Today it can be observed that precipitation increasingly falls as rain, the permafrost soil is thawing and much more melt water is flowing from the glaciers. Since 1850 the size of the glaciers in the Bernina region has shrunk by more than 30%. Moreover, some skiing areas in the Upper Engadin are situated on permafrost soil — global warming brings the danger that the masts of the transport installations could become unstable.

Climate Change

The Retreat of the Glaciers

The length of the Morteratsch Glacier shrank by 76.5 metres in the year 2003 alone. Smaller glaciers have suffered significantly greater reductions in relation to their original size than the larger glaciers. The locations and sizes of the glaciers that still exist today, and the areas they have lost since 1850, are illustrated schematically on the map. It is noticeable that the largest ice flows are clustered in the central region with the highest peaks, and are considerably larger in the northward-facing valleys — thanks to their sheltered position from the rays of the sun — than in southward-facing valleys. It can also be seen that the glaciers diminish in size at the edge of the mountain range, where the peaks are lower and the glaciers consequently have less ground surface to potentially feed them, and that in the side valleys only tiny residual glacial areas remain.

According to climate projections, five smaller glaciers will disappear in the Bernina region in the next five years. With a rise in temperatures of 1.4 °C, 30 glaciers — or nearly half of the total — would disappear between 2035 and 2075. By the end of the 21st century, 45 glaciers — two-thirds of the total — would disappear. Only the upper parts of the Morteratsch, Roseg and Tschierva Glaciers would survive following a further rise in temperatures.

Thawing of Permafrost

Permafrost occurs widely in the Alps higher than 2,000 metres above sea level, and thus represents an important aspect of the Alpine habitat. Permafrost is subsoil that reaches temperatures below 0 °C for at least two years. Due to global warming the permafrost is thawing out, which increases the risks arising from natural threats. Permanently frozen debris is protected by impermeable ground ice from erosion by flooding and rock slides. Thus the potential dangers are substantially reduced by the permafrost. If the permafrost ice melts, larger quantities of debris are subjected to flooding, and rock slides can occur. Moreover the potential for damage is increased by the growing use of hazardous zones that were previously avoided, despite the fact that permafrost is unsuitable for building on due to its constant movement. Measurements have shown that the permafrost reflects climate changes: the warmer the external temperature, the higher is the limit above which the soil remains frozen throughout the year and the deeper the permafrost boundary sinks in the soil.

Defence Measures

Avalanche/Rock Slide Barrier, Pontresina

Above Pontresina, on the Schafberg mountain in Val Giandains, is a permafrost zone. Here, creeping permafrost makes it difficult to erect defensive structures because the ground is constantly shifting. Today the Giandains avalanche barrier provides the necessary defence for inhabitants and visitors in Pontresina against avalanches and rock slides. It is situated at the foot of the mountain, which means that the structure is on stable ground and cannot shift.

Barrier Project: Technical Data

Maximum barrier height (mountain side) 13.5 m

Maximum barrier width 67.0 m

Barrier lengths 2 x 230 m

Retention volume, avalanche 240,000 m

Retention volume, rock slide 100,000 m

Time to construct c. 2 years

Completion 2003

Samedan Flood Protection Project

In the 1950s, Samedan was hit by several floods causing large amounts of damage. Dykes were built at that time and protected Samedan from further floods for many years. But today there is a fear that, in the event of exceptionally high water, the river could burst its banks and become a renewed threat. The community of Samedan plans to improve its high water defences with a flood protection project. At the same time it is also hoped that the project will bring enhanced ecological quality and permit renaturation of the river course. With this objective in mind, the dykes erected in the 1950s will be demolished and the old bed of the River Flaz returned to nature. The new Flaz will be diverted away from the village. Different types of profile will offer maximum protection from flooding as well as an ecologically valuable habitat for flora and fauna.

Climate Education

In order to make the effects of climate change on the locality clearer and more tangible, educative and adventure paths have been created in the Upper Engadin on a range of climate-related topics.

Tourism in the Upper Engadin

The villages of the Upper Engadin lie between 1,700 and 1,850 metres above sea level. Their centres are marked by old, well-preserved or renovated typical Engadine houses. The world-famous St. Moritz is the meeting place of the rich and famous, especially in winter. Here, according to legend, the basis for winter tourism in the Alps was laid as the result of a bet by the then manager of the Hotel Kulm with a group of English tourists.

In the Upper Engadin it is mainly the winter season that is important. For skiers and snowboarders, a total of 56 lifts and 350 kilometres of well-prepared slopes are available. The valley is also ideal for cross-country skiing, and attracts up to 12,000 sportsmen and women every March for the Engadin Ski Marathon. In summer, Upper Engadin offers a wide range of hiking trails for walkers. The five Upper Engadin lakes are an attraction in both summer and winter.

The Upper Engadin is reached by car via the Julier or Albula Passes. The Rhaetian Railway runs from Chur through the Albula Tunnel to St. Moritz and over the Bernina pass to Poschiavo. Local public transport services in the Upper Engadin are operated by the Engadin Bus Company.

A major problem in the Upper Engadin is the rapid spread of second homes, which are often occupied for just a few days each year. These homes take up a great deal of space, and the necessary infrastructure (connections, roads, electricity, water, etc) must also be laid on. The huge demand for second homes increases pressure on the local housing market (especially in St. Moritz and Sils). Local people can no longer afford the high prices and move away. In a referendum in the autumn of 2005, the electorate of the Upper Engadin voted for a law to restrict the building of second homes throughout the district.

I. Cotti, T. Frutig, A. Weibel; Ü: J. Attfield