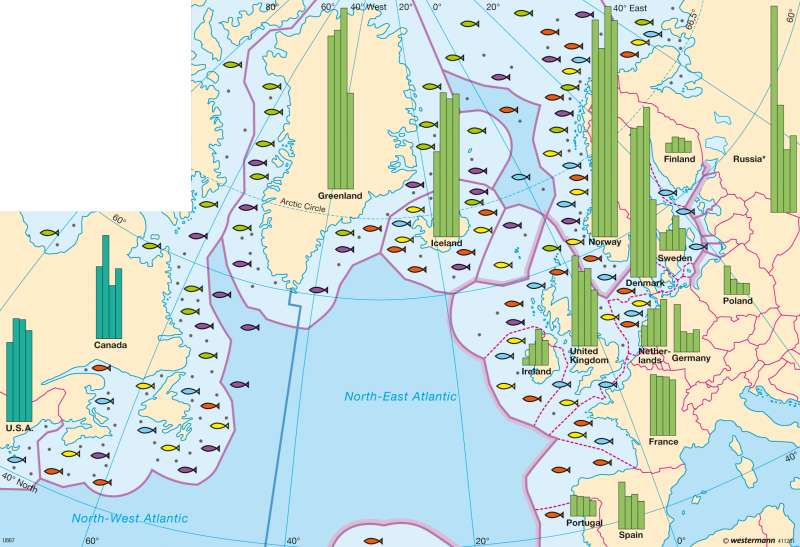

North Atlantic Ocean — Sea fishing

Northern Europe - Resources

978-3-14-100790-9 | Page 62 | Ill. 2

Information

After the North-West and South-East Pacific, the North Atlantic is one of the world's most important bodies of water for fisheries. This applies especially to the North-East Atlantic, which however has been classified as overfished for many years. While in the North-West Atlantic it is mainly edible fish that are taken, such as cod and ocean perch, in the North-East Atlantic purely "industrial fish" play an important role, like the capelin, a small cousin of the salmon, as well as sand eel, Norway pout and hake. Industrial fish are nearly or entirely unsuitable for human consumption, and are processed into fish oil and fish meal which is used as fodder in poultry and pig breeding, and in recent years increasingly also in aquaculture.Fisheries Policy and Quotas

On the initiative of Iceland, from the mid-1970s onwards national territorial zones were created in the form of 200 sea-mile zones. As well as for Iceland and Ireland, this parcelling up of fishing areas — which led to considerable international tensions because many fishermen lost their traditional fishing grounds — was of benefit especially for Canada and Greenland with their high proportions of coastline. For most countries of Europe, on the other hand, this arrangement resulted in losses.

By this time the pressure on fish stocks in the North Atlantic had already greatly increased due to the use of highly modern fishing vessels and trawlers. In the 1960s, initial efforts to protect fish stocks by means of international agreements to restrict fishing seasons and limit the numbers of fishing vessels remained ineffective due to the lack of systematic controls. In the 1970s, catches reached their historical peak of nearly 3 million tons in the North-West Atlantic and some 6.5 million tons in the North-East Atlantic, but soon after this the first signs of significant overfishing emerged — and fishing catches collapsed. In 1983 the basis for a Common Fisheries Policy was laid out within the European Community, but only on paper. As the Commission could only make recommendations but was completely powerless when these were not adhered to, overfishing continued and even increased: in the years from 1970 to 1992 alone the number of fishing trawlers doubled, and the number of smaller fishing vessels also increased significantly. It was only after catches dramatically collapsed in the 1990s that the goal of stabilizing fish stocks was pursued more resolutely, with stricter controls and the setting of quotas.

Reasons for Overfishing

The most important source of the former wealth of the North Atlantic fishing grounds is the high production of plankton in this region. This, in turn, takes place due to the vertical mixing of the water mass and the inflow of fresh water from rivers carrying mineral nutrients. But for some decades these favourable ecological conditions, especially in the biologically highly-productive continental shelf area, have been counteracted by a whole series of ecological burdens, including runoff of heavy metals, acids, nitrates and phosphates, and oil pollution.

Adding to the severe pressure on fish stocks from the unrestrained use of modern fishing techniques and overcapacity in national fishing fleets, there are also further problems. Firstly there is illegal fishing, which is also widespread in the North Atlantic and which, according to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) in 2006, now accounts for nearly one-third of the plundering of global fish stocks. A second grave ecological problem is the immense proportion of "by-catches", consisting of juvenile fish and various other sea animals that cannot or may not be processed and are therefore discarded into the sea dead as "trash fish". According to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), 30 million tons of sea animals per year are still being senselessly destroyed in this way; before the global ban on drift-net fishing this figure was many times higher. Fishing for sole, an especially popular edible fish, results in a by-catch of some 80 percent, while in shrimp fishing with its very fine-mesh nets the proportion is even higher. Moreover, extremely destructive methods have been and still are being used in industrial fishing, such as the bottom-trawling dragnets that are used to catch plaice and shrimp, which plough across the ocean floor and devastate all life there.

K. Lückemeier; Ü: J. Attfield