Foreign labour

Europe - European regions

978-3-14-100790-9 | Page 41 | Ill. 4

Information

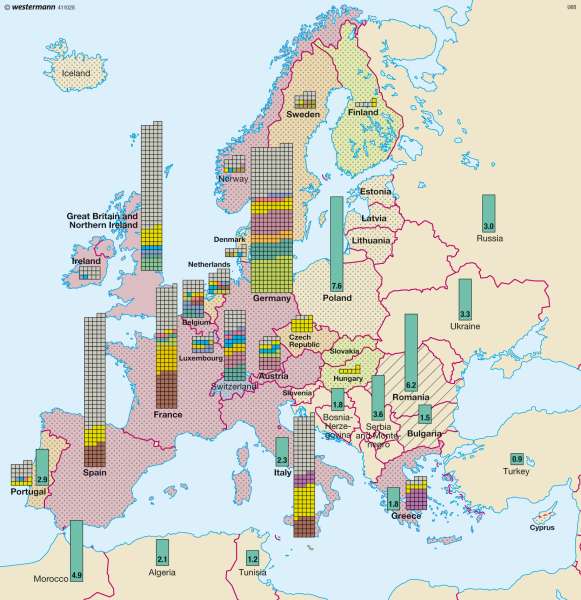

Patterns of mobility across European national boundaries have changed markedly over the past several decades. The streams of guest workers seeking employment in other countries reached historic proportions during the 1960s and 1970s. These migratory movements were triggered by an economic upswing in the industrialized countries during the post-war period, by the resulting demand for labour and by the gap in economic development between those nations and countries on the fringes of Europe. A second wave of immigration took place during the ten-year period from 1988 to 1998, when the number of immigrants living in Europe rose by 36 percent to nearly 19 million. During this phase, the ratio of foreign nationals to native citizens rose primarily in such countries as Finland, Denmark, Spain, Portugal and Italy, which had previously hosted relatively low percentages of immigrants. Although Germany experienced a temporary boom in immigration as a result of the admission of civil war refuges from the former Yugoslavia, a policy of deportation, incentives to return home and isolation brought about a decline in the relative size of the immigrant population.Recent developments

The foreign population continues to rise both in absolute terms and as a proportion of total population despite this policy of isolation. This is attributable primarily to the fact that, contrary to expectations, many of those immigrants recruited to the labour force temporarily during the 1960s and 1970s have formed relatively stable "communities" which are now composed of the second and third generations of the original guest-worker families. Consequently, host countries have been faced with the challenge of promoting long-term integration. Moreover, several European nations, such as the Netherlands, Spain and Great Britain, welcome immigrants from their former colonial territories, which explains the high percentage of North Africans within the foreign population in France, for example. A significant rise in migration has been noted in recent years as the result of the influx of highly qualified temporary immigrants and seasonal labourers. The result is a substantial increase in the proportion of citizens from other EU countries in the Member States of the EU, although immigrants from outside the EU still account for a larger share of total population in these countries. As a rule, these workers remain only for a limited time in their host countries, either because their employment contracts are limited or because they are reassigned to other locations within their companies. This situation appears likely to change with the implementation of green-card systems and the possible introduction of a blue card for highly-qualified individuals from non-EU countries hired by employers in the EU.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, nearly all of former East Bloc nations experienced substantial waves of emigration. This development is largely attributable to the weakness of their economies compared to those in Western Europe and to the influence of the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia as well as numerous other ethnically motivated conflicts in other regions. The situation has stabilized, however, in those countries in which the process of political and economic transformation has progressed rapidly (such as the Czech Republic).

Migration patterns change constantly under the influence of political, economic and social factors and developments. Although France, for example, was the primary magnet for emigrants from North Africa until well into the 1990s and remains so for Algerians even today, Moroccan and Tunisian nationals in particular are opting in increasing numbers for emigration to Spain and Italy. Ireland, once the "poorhouse" of Europe, has become a host nation par excellence. The tremendous economic boom in Ireland in recent years has resulted in a dramatic rise in the proportion of foreign companies and employees since the mid-1990s.

The ratio of foreign nationals to total population differs considerably from one European country to another. Foreigners account for seven percent of the population in Finland, and only slightly more in Germany (nine percent), whereas they make up more than 30 percent of the population of Luxembourg. Germany is the European leader in absolute numbers of foreign workers, followed by France, Italy, Great Britain, Spain and Switzerland.

K. Lückemeier; Ü: J. Southard